We hauled our heavy packs on with pounding heads to catch the boat from Puerto Williams to Puerto Torro. This would be a 3ish hour boat ride, for free since it was a weekly trip to deliver food and supplies to the Eastern port on Navarino Island where no roads go. We had indulged in the hostel party life until the funny hours of that morning (3 – 4 AM) and were feeling the effects of our choices. Nevertheless, we had made sure to have our bags packed and ready to go before we allowed ourselves to join in on the fun.

The boat was quite small when we arrived at the dock, just across from the hostel. We hadn’t had a boat adventure since the ferry trip down and I was curious about how rough the waters would be farther South in the Beagle Channel. We hopped on the boat with a new hostel friend who would also be visiting Puerto Torro. He earned the nickname (unbeknownst to him) of “Shadow,” because it seemed like wherever we were he was right there at our heels. But, he wouldn’t be joining on this hike, only visiting the town.

Our plan was to hike West from Puerto Torro, over the pass of Mount Misery, and down to Lago Navarino. Here we would set up a camera, then hike North to Laguna Rojas, and set up another camera. From Lago Rojas, we could wait at the end of the road for a weekly bus… as long as we made sure to get out on time. We read that the bus ran every Tuesday and Thursday in the evening back to Puerto Williams. The trek from where the boat dropped us off to where the bus would pick us up would be about 35 kilometers. There weren’t any trails we could find on any maps or apps from Puerto Torro over to Lago Navarino, nor from Lago Navarino to Lago Rojas. There was, however, a marked trail on Caltopo for the very last 5 kilometers or so. We had no idea what would lie ahead.

The boat engine fired up loudly and gurgled in fuel. Despite this, Nacho fell asleep instantly once we sat down, after dawning a life jacket just to be safe (we weren’t required to wear one inside the boat, only out on the deck). I let him peacefully sleep for a bit but then got too excited seeing sea lions pop out of the channel and nudged him awake to come watch them with me. Some groups of the sea lions were so big, I never knew they congregated in such massive groups! We would pace the narrow back deck from side-to-side scanning for marine life until we got too cold, then we’d clamor back into the cabin to warm up. Our captain was a spitting image of Ron Swanson, and I don’t think he smiled or spoke a word for the entire trip to the port. Not that he seemed unfriendly, just very focused.

As usual, as soon as we stepped foot towards the trail, we had a doggo friend. This guy was an older German Shepherd with some scars around his mouth, likely from getting snagged in barbed wire. We hoped he wouldn’t follow us the whole way like our past companion since we wouldn’t be completing a loop this time. We did not want to become the local island dog-nappers.

It took a whole 5 minutes to walk across the Navy base/town on muddy dirt roads. The road faded as we veered off behind a water station to find the start of our hike. A glimpse of what the rest of this hike was about to be greeted us. The forest was the densest we had encountered yet as we began to ascend the steep pitch up to the pass. We were making no progress whatsoever, not even the dog. As we fought our way up, Nacho claimed he thought he must be sweating whisky. I wasn’t feeling quite as rough, but was definitely not firing on all cylinders. We made multiple breaks for rest and snacks without making much headway. Eventually though, we broke out of the forest, and into the “turba.” Turba is light, spongy, decomposed plant debris that forms in swampy places. It can include anything from spiky, hard mounds of plants, moss, or deep red squishy moss that engulfs your leg. The latter is basically like walking in deep, slushy snow. We were grateful for a break from the bushwacking in the forest, but the bog was its own beast to navigate through.

We found a rocky ridgeline that would provide a dry place to pitch the tent for the night. It wasn’t blocked from the wind, and weather was moving in, but it beat putting the tent in a swamp. We hoped the dog would return home as we heard the rain start to tap on the fly. It was a cold, restless night. And a bit eerie. There didn’t seem to be much life up there on the East side of the island, but we both couldn’t shake the feeling of being watched. As a horror movie junky, I sometimes assume that I just set myself up for these moments by putting all the monsters/ghouls/maniacs into my mind from watching the films. But Nacho actually mentioned it first, and the hair on the back of my neck prickled before I verbally agreed. It seemed that when I’d take my eyes off of where I was stepping to scan the horizon, I’d see movement somewhere in my peripheral. But I never could catch what it was. We didn’t make a fire that night, just cooked our ramen on the stove and quietly retired into the tent to sleep.

We woke up to some light blowing snow the next morning, a storm was moving in from the southern Pacific. We were relieved to see the dog must have returned home since he wasn’t curled up by the tent like the night before. We quickly broke down camp and started to move, it was cold. We made our way a bit higher up through more turba. I decided to bring waders after our Lake Windhold adventure, and since my hiking boots were losing more structure with every kilometer we walked and were now full of holes. My feet were happy and dry in the waders, but I struggled making the high steps through the bog with the heavier pants tugging at my knees. I was also sweating profusely with the lack of breathability.

The wind howled harshly and freezing rain pelted our faces as we crossed over the pass. We were hopeful that once we dropped down into the ravine on the other side we would be protected. This did end up being the case, however the ravine choked up quickly. As the river narrowed and the channel slotted up, our pace slowed again, and navigation became tricky. We stretched the ability of our wellingtons/waders to smear and stick to increasingly slick and steep rock on the sides of the canyon and hopped up and over fallen logs. Our pace crawled to molasses speed. Nacho was cold and wet from the rain penetrating through his layers. So when he slipped and plunged hip deep into the icy stream waters, it didn’t take long for him to raise the alarm that he may be starting the early phases of hypothermia. We ditched the ravine and crawled up fallen trees and through loose mud up to the top where there was some flat grassy areas. I threw up the tent and made a nest of the sleeping bags while he started to shed the wet, cold layers. Once he was in his sleeping bag, wrapped in an emergency blanket, I boiled water for hot tea and soup. It took a bit, but eventually he could feel his feet again and stopped violently shivering. We were happy we were prepared in case one of us got cold, but it was not an assuring way to start a 5 day trek in the now quickly approaching winter.

We stayed high the next morning, above the ravine, and followed a better path of least resistance down. We could see Lago Navarino in the distance but knew from our slow pace and lack of trails that it would still be a while before we hit the shores. I decided to go with the waders again, it seemed like warmth was more important than flexibility here. We walked down the gently rolling slopes and back down into the thick forest. Here, we would be presented with choice after choice about which way looked less hellish and may actually get us down to the lake. It was either thick brush, tight saplings that our backpacks would get wedged between when we passed through, or a lovely plant called Winter’s bark. Winter’s bark, Drimys winteri, is a small evergreen tree with thick, soft leaves and, in summer, big white flowers. It’s a beautiful, and preferred to bushwhack though due to its bendy branches. However, with the flexibility came the risk of getting whipped sharply in the face or ears as the branches sprung back. On one stretch of especially hellish bushwhacking, the “f^%$ around find out” phenomenon seemed especially relevant. I shared my thoughts with Nacho and tried to relate this ridiculous idea of ours to link the lakes in the manner we were trying to by saying, “You know, if you don’t f^%$ around, you’re not going to find out!” And we found out why there wasn’t a trail linking the port town to the lake.

Eventually, we hit the shoreline. Alas, we could cruise the coastline. And it didn’t matter if there wasn’t a nice rocky beach to follow, we had waders/high boots so we could just walk in the lake! We set up the first camera at the Northern end of the lake. Ultimately, we decided that when we come back to retrieve the camera and collect the water sample, we would not do the multisport adventure loop involving the boat to Puerto Torro and bushwhack up and over the pass. Instead, we would just come in from the road on the North (where we planned to end this trek) and do an out and back instead. We set the camera at the northern most point of the lake for future Kelly and Nacho to have a bit of an easier time.

On the map, between Lago Navarino and Lago Rojas, was a 13 km stretch that looked boggy on the map. We hoped that we could get up into the forest on the edge of the bog and try to find a path of least resistance there, hugging a contour line on the map to not gain or lose too much elevation. We left the lake and hit Lago Pollollo. But from here, we couldn’t see an easy way up into the forest, and the beaver damage was so bad it appeared we would be log hopping the whole time. Our shins were still beat up from the last steeplechase adventure, so we pivoted our plan and headed for the bog. This bog was full of the deep, red moss that liked to eat legs. As we tried to powerwalk through, we thought of any way to humor ourselves as our legs were screaming. Nacho gave us each a nickname – “Kelly Iron Calves” and “Nacho Ground Squats”. We were desperate for any humor or fun during this unending stretch of bog.

It took us nearly all day and into the evening to finally make it Lago Rojas. We got a bit turned around just before reaching the lake. Perhaps it was iron or something in the soil, but Nacho’s compass wasn’t working properly and would spin at times. My mapping app was also jumpy and not giving accurate readings. The clouds hung low and the forest was dense so we didn’t see many landmarks or signs of how to tell which way was North. Occasionally, we’d find flagging in a tree from someone else who tried to make their way through here. But the flagging must’ve been years old with how brittle it was, and the marks seemed isolated. We couldn’t find any other markers nearby them when we did stumble upon one.

Once down at the lagoon, we found a place to make camp in a dense forest of short beech trees. Nacho built a fire while I set up camp and we feasted on our usual paste – instant potatoes, soy protein, and a soup mix. We tried to dry out what we could around the fire, but soon rain and wind pushed us into the tent.

The next morning, we broke camp in the cold and quickly hightailed it out of the shady forest. We found a good spot for the camera trap on our route North, and quickly set the camera and tuna lure after so much practice. It seemed quicker to use the waders/wellingtons along the coast again, and in no time we hit the northern shore of the lake to where the cow trails would lead us to Caleta Eugenia (the end of the road). We still had the usual beaver dams to navigate through, but to our surprise we breached the forest and saw the grassy slopes down to the Beagle Channel in no time. We made our way to the road, dropped our packs, and collapsed on the shore. This one was a toughy. From the schedule we took a photo of on the door of the hostel, the bus would be arriving around 4:30 PM, so we had a couple of hours to enjoy the sun and eat the last of our snacks.

Half past 4 came and went, then 5 came around… no bus. The sun, and temperature, were dropping and now we had eaten the last of our food reserves. We didn’t have cell service, so Nacho tried his radio to call in to the CONAF forest service to see if the bus was coming. No luck with the radio. We looked back at the photo we took of the bus route. In small print, above the hourly schedule, was one simple sentence that both of us missed. “This service will be available until April 30, 2023.” It was May 2. Caleta Eugenia sits 23 kilometers East of Puerto Williams, at least a 5 hour walk. We were cold and out of food, and tired after our 5 day adventure. We could camp and do it in the morning, or we could see if anyone was home in the abandoned looking farmhouse at the end of the road. There was livestock around, so maybe someone lived there? We paced and balanced our way back and forth across some drift wood weighing the options. If we started walking back, we were kind of committed to walking unless a car passed by, which would be unlikely at night. Or, we could try the farm and ask to pay for a ride, though neither of us were carrying much cash.

Just when we were about to start walking, a shuttle bus blew past us. We watched eagerly to see if it was the local bus, though it looked like a private ecotour bus. But it was empty. The bus didn’t brake but we recognized the girl in the passenger seat as a French girl who had been volunteering at a nearby workaway and had visited the hostel to make friends. We wondered what they were doing as we waited by the road for another 20 minutes to see if they were coming back and if we could catch a ride. Eventually, they did return, and it was the shuttle service! We happily climbed into the warm cab and tried to keep conversation amongst our delirium on the drive back.

Over the next few days, we dried out our gear, gave Savannah a make-over since the dampness here was making her a bit moldy, and prepared for the next stint of adventure science. The brake pump arrived in the post so we played with how to make it into a water pumping device to syphon water through a filter small enough that could collect the environmental DNA. We were pretty happy with our first prototype and eager to give it a try in the field. We took a break from van/tent life and rented a little off grid cabin by the coast. The host granted us an early check in and late departure time. It was a lovely place to rest and recover.

At this point we had walked most of the eastern and central valleys and mountains of the island. Now it was time to explore the western side. I had seen that there were some trails marked on the maps of a 5ish day circuit starting at Rio Lum, then south to an abandoned radio station, then up North on the western coast of the island. It was about 50 km in total. This would be too big of a trip to have time to repeat (since we already had a few multiday treks to repeat by then for sampling), so I thought of only putting one camera out on the first day, then making the rest of the hike a “leisure” hike. We would also put out a few more cameras along the 55 km stretch of road. These only required short half hour hikes or so to be easy to retrieve and were still set on water bodies of interest. We spent one day on the drive out setting up these sites, then parked at the Navy base at Puerto Navarino for the night and slept in Savannah. Nacho talked with the commander at the base about our hiking plan and if he wouldn’t mind keeping an eye on Sav while we were away. He thought our plan was crazy to do this hike, it was not visited often, but he would watch the van.

The next morning we started the trek with heavy packs and our thumbs ready to hitch a ride on the 17 km stretch of road we needed to backtrack from the base to Rio Lum, the start of the trail. It was a Wednesday, so we were hopeful there would be some traffic on the dirt road either from day trippers, construction workers, or the lumberjacks that harvested the wood for the city. After 7 km and only a few truckers passing by, our hopes were dwindling. We had been a bit overconfident about catching a ride it seemed. We were just about to drop packs and take a break, when we heard a pickup truck making its way down the road. They actually stopped! We threw our packs in the back, on top of the construction equipment, and hopped into the rear seats of the cab. The truck raced off before we even could buckle our seat belts. We drifted around turns and both Nacho and I were convinced the truck was going to roll, twice. I kept checking to see if our packs were still with us. We held on to whatever we could and were relieved to see our stop coming up. Nacho was a bit shook about how dangerous the guy was driving, though we had been warned earlier that locals drive that road fast. I can’t confirm if we will try hitch-hiking again here.

A few dogs bounded across the farm at the start of the trail and one took a liking to us. He was black with grey on his face and paws. As we set up the trail, he trotted ahead, as if showing us the way. The trail was well marked and we broke our promise of verbally acknowledging this, now having a superstition that as soon as we say a trail is in great condition it disintegrates. We followed a gradual slope up along Rio Lum and placed one camera about 2 km from the road. Future us would be happy for just a short day hike, and the river looked like it could be minky. (Mink are one of the invasive species we are interested in detecting with camera traps and environmental DNA sampling). We camped a bit farther up the trail and were treated with FM radio reception through Nacho’s radio to listen to some latin tunes while we watched Ushuaia light up across the channel.

The next day, the trail took us higher up to Paso Miadino. We were shocked to find beaver dams even at this altitude. And perplexed to find so many beaver skeletons. Without natural predators, we tried to rationalize why so many of them were dead. If dogs, such as our companion, did hunt the beaver, their bones would likely be scattered after the dog fed on the meat. And if they were hunted, even just for the fur, the pelt wouldn’t be rotting next to the bones. Days after we returned, we found out it was likely due to over competition. At high altitudes, there aren’t many trees. So if the invasive beaver populations up there used up all of their resources, they would just die. Our dog friend, who we also named Shadow, found one of these beaver pelts and was the happiest dog in the world whipping it around and gnawing at the meaty bits left on it. Nacho and I nearly gagged.

We reached the highest point of the pass around nightfall. It was cold and windy, but just beautiful up there. We were now on the western side of Los Dientes (The Teeth) from the circuit we had done before. Moonlight reflected off the spires of rock and the shapes of the mountains were mystifying. I didn’t want to leave. Hours were ticking by though and we still had a long way to go to our camp destination, an old radio station that we were hoping we could sneak in to and sleep. We started dropping into the valley of Rio Matanza just as it became dark enough to need headlamps. Apparently we hadn’t learned our lesson from the last sufferfest since we were fooled into following the gentle river down into a deep ravine. Scrambling on rocks and log hopping ensued as we got deeper into the belly of the canyon. We had lost the trail again, and cursed ourselves for speaking the forbidden words the day before of how well it seemed to be maintained. We pushed on until around 11 PM before we decided to abandon the ravine, we were moving too slow and needing to backtrack when we’d hit a waterfall without a way to climb around. We climbed up out of its depths and haphazardly stumbled onto the trail, what luck! Bright red lines against a white square marked the trees on the trail down to the radio station. We arrived around midnight. Our sleeping plans changed as we realized the station had now been turned into a museum, which was unfortunately closed (it did look cool through the windows though). We pitched the tent behind the building with Shadow curled up next to the rainfly.

Shadow presented a bit of a problem since this hike was also not a loop trail, but more like a “U.” He didn’t return home the first night though, so he was now stuck with us on this trek and would be dropped off on our return. We shared some of our jerky and hard boiled eggs with him, since the hike was tough work for just a few nibbles of beaver pelt.

The next day we picked up the trail again and had false hope, again. After about a kilometer, the maintenance of the trail diminished as well as our hopes of getting to Puerto Inutil (Useless Port – maybe because it’s too shallow?). It appeared that only the trails very close to the new museum were being maintained. The next couple of days from this point are a bit blurred. Lots of bushwhacking, hiking into the middle of the night to make up mileage from slow travel, log hopping, some four letter words, muddy feet, and 3 goofy souls wandering through a lost part of the island. We’d hike until we would become delirious and set up camp wherever we could find a flattish patch of dirt. The trees were still marked with the red equal sign against the white square, but at this point about half the trees had fallen over so sometimes we had to scan the ground for markers. At night we developed a system to not lose the trail, after losing it too many times before and needing to backtrack. It was sort of like swinging leads climbing. One person would wait at the last trail marker while the other searched ahead, sometimes for just a few seconds, sometimes minutes, then would call back that they found it and the other person would then look on ahead. This “game” was especially necessary at night when it was nearly impossible to tell where the trail would have gone back when it was maintained. I’d still see the red equal signs in the dreams at night in the tent.

Over three days we skirted North to Puerto Inutil then due West to the coast. In the bay we found a plethora of jellyfish and some old whale bones washed ashore. I have no idea what kind of whale but it must’ve been huge! The vertebrae were bigger than my waste and ribs longer than I am tall. Sometimes we would scramble along the rocky shoreline, which seemed way better than stepping over fallen trees. Shadow turned out to be quite the climber and only needed help once on a downclimb. We were quite the adventure team.

After leaving the bay, we hiked up another pass to Lago del Medio which, no surprise, was also ravaged by beavers. It seemed that no part of the island was untouched. We crossed up and over the pass, ended again at night and set up camp near shore. We were lucky to have a final day of the trek to be full of sun and warmth, and stunning scenery. Across the Murray Canal, Hoste Island teased the mind with potential hikes and climbs up the snowy, prominent peaks. When I wasn’t watching my footing, I was staring across at these giants making a promise to go and visit them someday. The Dumas Peninsula, where the mountains are on this island, is so vertical that there aren’t any inhabitants… there’s no flat place to put a house!

We arrived back at Savannah in the evening like a troop of wounded shoulders, the hike completely trashed us and our gear. Achy joints from hobbies that batter bodies spoke up. My gators were hanging on to my leg only by the magic of duct tape. Even the dog was limping. Perhaps I had pushed it a bit too much on this “for fun!” hike, but it was a thorough adventure and one that won’t be forgotten. Back in town we found out that the trail hadn’t been maintained since 2006, which answered a lot of our wonderings about its condition. We will never take a trail for granted again.

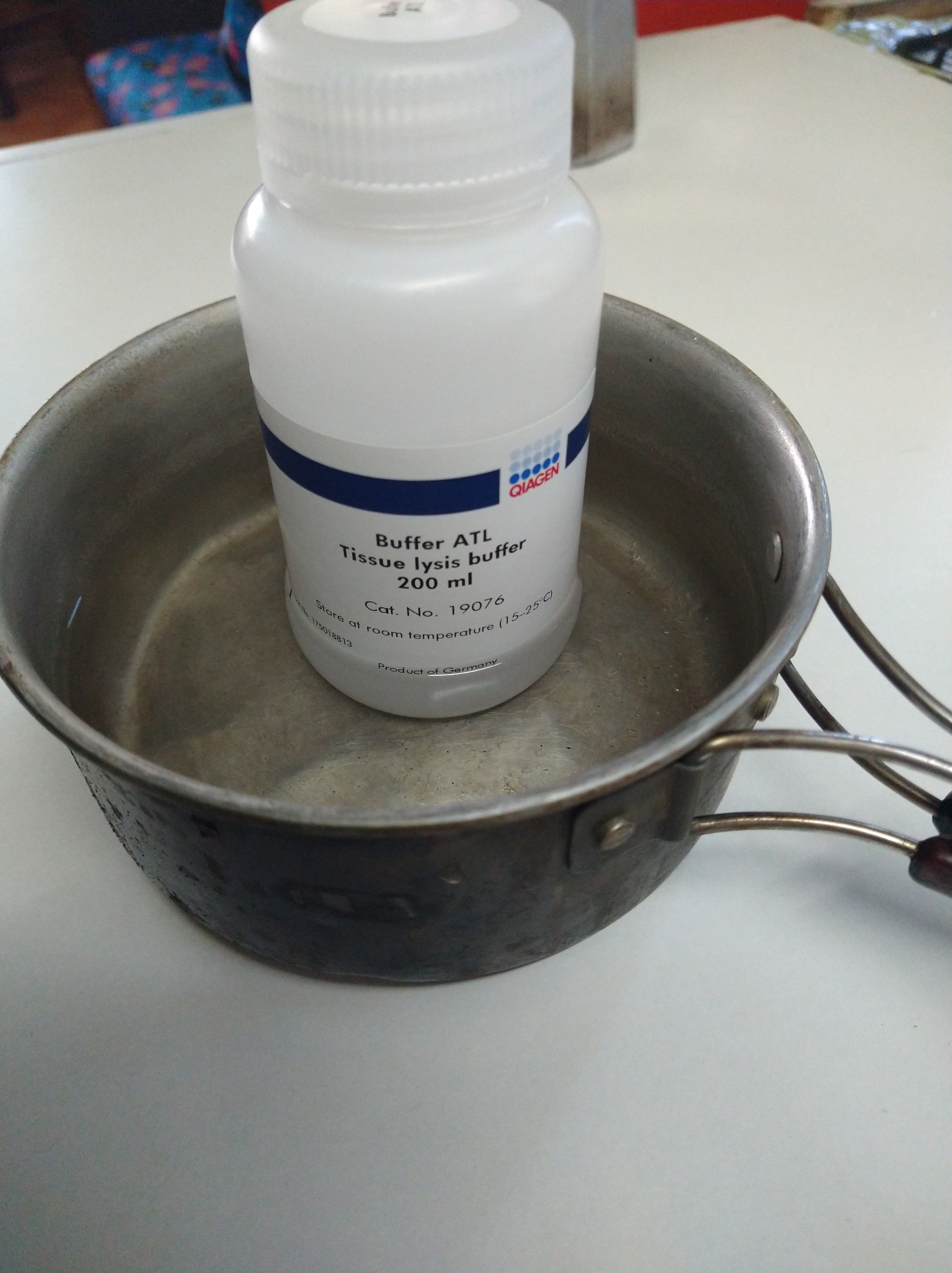

The trip with Navy to the other islands of the Cape Horn was quickly approaching, but we still had some time (and pressure) to start retrieving the cameras we had placed and collect water samples. We fine tuned our water pumping device and set up sampling kits on the kitchen table of the hostel. We would pump 3 liters of water (1 L per replicate, 3 replicates per site) at each lake or river site. The filters are made of cellulose nitrate and have 0.45 um pores for the water to pass through, but for cells to be collected. The fancy funnel filters cost more than the amount that the university could budget for this study so, like the pump, creativity was necessary. I could order sterile funnels and the filter papers separately for quite cheap. With the proper folding, the filters could be placed within the funnels and the funnels could be attached to the silicon hose that ran to the air tight water bottle, then to the brake pump. It worked beautifully, besides the fact that the filter paper was much more brittle than I assumed and usually broke into four triangular pieces that I would then fit into the funnel. After the liter of water was passed through the filter, the paper would be carefully folded with sterile tweezers and placed into a prepared tube (also done on the kitchen table) with a lysis buffer that preserves the DNA. When this buffer is cold, it forms a precipitate, so before adding 1 ml of buffer into each tube, it had to be heated to about 56C. A kitchen pot with some luke warm water sufficed. If there’s a will, there’s a way.

After water collection, we removed the cameras and excitedly looked at the trail cam data. Pretty cool what was captured! Animals ranged from our target species of mink and feral dog, to feral pig, beaver, and lots of birds. The white-throated Cara Cara is an especially cool catch, these birds are only present in high alpine areas and rare to see!

Here is a screenshot of the Caltopo map we’ve been using for hikes and camera/sampling:

Finally got around to updating the map, here!

I was so happy to see a post from my favorite world class adventurer !! I have to admit I am exhausted just thinking about the long treks, the cold, the dark…..do you ever miss your cozy bed at home? I guess not because I truly believe you are doing what makes you happy and doing an amazing job too! Stay safe …..

Love you Kel Kel

There is a possibility that I might see you in August … I hope so!!

LikeLiked by 1 person