The Amboseli Baboon Project in Kenya is one of the longest-running studies on wild primates in the world, spanning over 50 years. Hundreds of known individuals, in various social groups, are tracked and observed daily. We’re interested in what’s going on at the individual, group, and population levels of this species, and we collect data on the genetics, hormones, nutrition, and relations among themselves and with other species. My goals at Amboseli National Park were to deploy a “sample to DNA sequencing dataset” protocol completely remotely – this means extracting DNA from a fresh baboon fecal sample, then amplifying (making copies) of genetic regions that hold mutations (SNPs) or microsatellites (STRs, repeated base sequences), and then sequencing these regions across multiple individuals to assess relatedness. Basically, we want to know whose kid is whose and how their genetic backgrounds affect social behavior. It’s easy to tell mother-offspring relatedness due to the presence of maternal care, but it’s not so easy to know who the father is. If successful, this protocol will reduce the headache of permits to get biological samples out of Kenya and into Germany, provide a faster turnaround time for results (the whole protocol could be completed onsite within a couple of days compared to months needed for an export permit), and provide the opportunity to train the field staff on site. I went down to the Amboseli field site for the first time in late February to do this pilot study. Since I was hired in October 2023, I’ve been optimizing this protocol in the lab. But, in the lab we have sterile conditions, uninterrupted power and internet, and easier access to chemicals/equipment/etc. I felt pretty dialed on the wet lab work here in Germany, and I was quite curious how I could replicate it in the field in Kenya.

The flight from Germany to Kenya is about 9 hours. I would be bringing in chemical reagents (on ice) that I would need to run this protocol. These buffers/solutions are not necessarily restricted, however with customs it’s always a game of chance on who you get to search your bag. A cooler full of frozen tubes labeled with science jargon may not be what the TSA agent wants to find. While packing, I placed a styrofoam cooler with the ice packs and frozen tubes in my bag, with supplies like tubes/tips/gloves around it. Then I added my field clothes around that to sort of pad everything. I’d also be bringing a separate duffel bag full of trekking supplies since I planned to meet up with a friend from South Africa after field work to trek on Mount Kenya. Finally, I’d bring a small daypack with my work laptop, the MinIon sequencer (mini USB DNA sequencer that makes this all possible), and other electronics I’d need.

I was picked up at my flat by a taxi at 4 AM for my flight from Leipzig to Frankfurt at 6 AM. In the excitement I hadn’t really slept so I took a cat nap during my 3 hour layover before completely passing out on the flight from Frankfurt to Nairobi. I landed at 10 PM where I suddenly got some butterflies on what customs would be like and what my strategy would be, should I need to insist that I can bring this stuff through. My fear was that they may say I need to pay some sort of steep income tax since it was so much supplies, or they would confiscate it. My seat was in the back of the plane, so I was queued behind a couple hundred people getting through the passport check. I could see the luggage carousel past the counters and eventually, as the line got shorter, there were only a few bags left, including mine. Relieved they had at least made it down together, I grabbed them and walked towards security check with a fake it til you make it strategy. But, they only requested to search the handbag where my electronics were and didn’t even scan the science bag. I was clear to go and felt a huge sense of relief, everything I needed could come with me.

The hotel my work arranged for me included a shuttle and this was the first time I’ve walked out of an airport to find someone holding a sign with my name on it, though only nearly as it read “Kelly William.” Moses, the driver, quickly helped me carry my bags over to the shuttle. The ice was broken immediately when I went to hop in to the right seat and he exclaimed, “Oh so you’re driving the taxi now!” It had been a bit since I’ve been down here and I forgot the driver and passenger side were switched. We chatted the half hour or so to the hotel. He strongly discouraged my idea of taking public transportation, the matatu buses, up to the base of Mount Kenya (this is the cheapest way). He said it was both risky and would not be a pleasant experience as sometimes the buses break down or they give westerners a hard time. He also handed me his taxi card telling me he could do it at a discount, so there may have been a business angle to these warnings.

I arrived at the hotel around midnight, showered, repacked my bags, and set an alarm for 5 AM. I’d be leaving one duffel behind, with the mountain gear and cold weather clothing, with the staff at the hotel and bringing all of the science stuff and warm weather clothes out to Amboseli. I slept maybe 3 hours before the alarm went off and I jumped into field clothes, stopped by the lobby to drop off the mountain bag, and caught a shuttle to the Wilson airport. I would be flying in a small 5Y-SLL plane, similar to the one we traveled on in Alaska. There were a surprisingly large group of people waiting at the airport, but flying to Lake Victoria or other well known reserves for safari guides. When the Amboseli flight finally got called at 6:45 AM, 9 of us lined up outside of the plane. I saw my ticket said seat 3A and I hoped it was a window seat. After climbing in the tiny cabin, the pilot told us the seats weren’t assigned and we could sit wherever. He saw my big grin and asked if I wanted to upgrade to first class and sit behind him and the copilot. No sooner than he finished that question was I clambering to the front… turns out no one was racing me there though.

When the plane started up it jerked forward with power, almost like holding back a horse before giving him his head for a full gallop. We queued in a line, lots of flights were flying out in the mornings. Eventually it was our turn and the plane galloped ahead and launched in to the sky. It was cool to see how the pilots used the controls and what altitude we were reaching. We flew low across the plains, then up into the clouds. As we made our way Southwest, Mount Kilimanjaro appeared ahead. Still slightly snowcapped, but I later learned much of the glacier melted and was perhaps why the Amboseli valley was so flooded this year. It felt like as soon as we reached altitude we were on our way back down to our first stop to drop off some people for a safari. I had assumed this would be an airstrip but as the ground was quickly approaching, I finally noticed a dirt track we’d be landing on, how wild! Half the group got off the plane to load in to a safari truck, then we turned around and took off from the bumpy track again.

Dry, barren landscape quickly gave way to lush green grass and small lakes, all within 15 minutes from the last runway! I could see giraffe, elephants, zebra, flamingos, and antelope as we descended into the valley. This was nothing like I expected, especially juxtaposed to the arid landscape we had been flying over. This runway was paved and soon I had my luggage and was trying to figure out who I was looking for from the team to pick me up. A lot of field guides rushed to their clients, so I knew it wasn’t them. Eventually one of the drivers from the camp walked up from a truck asking if I was Kelly. We exchanged hugs and, after officially checking in to the Amboseli National Park with my park permit, climbed in the truck to head to the research station. He would patiently stop the truck and wait while I tried to take photos of the wildlife, and explained that with the heavy rains this month all of the animals were really healthy as compared to last year. We saw herds of huge African elephants and plump zebra. Tons of flamingos enjoyed the lakes. It was about a 15 minute drive from the airport to camp and I couldn’t believe how many different species I was seeing!

The team at Amboseli gave me a warm welcome and for the next 10 days I truly enjoyed working with and getting to know everyone. And I’m excited to continue work with this team over the next couple of years! The entire camp is solar powered, including the small remote lab where I would be carrying out experiments. There is a main kitchen/eating area in the center of camp, and tents surrounding this center for staff and visiting scientists. I was housed in a tent of one of the primary investigators who was not on site at the time. I wish I could live there! It sort of felt like a tent meets a yurt with ample space, a big bed and desk, and a few pieces of furniture. I’d keep the doors open (but the screen closed) at night and had some of my best sleep in a while… despite being woken up occasionally by sounds of elephants and lions nearby. The camp is surrounded by an electric fence, since it truly is out in the savannah and wildlife moves through the area. However, some make their way in such as the vervet monkeys that would hang in the tree next to my tent, or the python that took up residence in roots of a tree near the kitchen. We found it on the first night I arrived and the cook nearly knocked me over rushing past it since he forgot his headlamp!

(Inside the tent on left, Lab pictured on right with solar panel)

I wanted to go into the field as much as possible, to collect my samples and also to have every opportunity to see the wildlife in and around the park. The study site was actually larger than Amboseli park and the baboons would even move across the border into Tanzania! We would leave the camp at 5:30 AM packing the local tea with milk (my stomach had to get used to this since milk isn’t really in my diet anymore), some bread with peanut butter or jam, and a banana. The field cars were little, but powerful, jeeps. Since we drive to where the baboons are, and not necessarily on roads, these little tanks are the perfect vehicle. And they’re light so they don’t impact the vegetation too much.

We would arrive to where the group of baboons we were observing slept in trees for the night. If the observers couldn’t find them from where they left them the day before, they would use an antenna to pick up the frequency of one of the collared individuals in the group. I got to help with this too and at one point I was holding the antenna out the window of the jeep listening over the headphones for a beep while the driver drove around trying to get a signal! Ideally, we’d arrive at the group before they came down from the trees, just around sunrise. I loved these moments of watching the sun change the colors of the landscape and Mt Kilimanjaro coming to life.

We would walk with the baboons for about 6 hours. As I mentioned, this project has been going on for decades, so the baboons are habituated to the team. Care still needs to be taken to give enough space to the animals and not affect their behavior. I was an additional person but usually the team would be 2-3 people out with a group of baboons. There are the observer(s) who would walk along with the baboons, take notes on behavior, and collect fecal samples opportunistically. The observers knew each individual baboon based on subtle physical differences… there are around 300 baboons we study, amazing to be able to identify each one! Then there is the driver, who would follow the group of baboons at a distance and be ready to pick up the observer should an interaction with a wild animal take place. The most dangerous animal at the field site is the African buffalo. I was surprised this big five animal was the biggest concern. Apparently though, when they are threatened, they immediately charge with incredible speed. They tend to be more aggressive in their adult stage. When I asked what to do if I encountered one, I was told that if I think I can run fast enough to a tree, do that and climb it, and if not that I should lay down. I hope I never have to make this insanely difficult decision in my life. We are also wary of elephants, especially since the baboons do not warn for them, if they’re not threatened/predated they won’t warn others in the group. Lions and hyenas are quite common in Amboseli as well. So that said, a driver is on standby at all times and if these animals are around it’s best to wait in the car until they pass.

My very first day in the field, we saw a cheetah. A CHEETAH. When I was a kid I was obsessed with cheetahs, probably because they’re fast. I’d write reports on them and give them to my parents. I’ve seen them in zoos but never in the wild, and apparently it was quite a lucky siting. On my second day I saw my first spotted hyena galloping across the savannah. That night we joked about what I would get to see on my third day and I told them I’d really love to see some lions. No joke, the next morning as we were driving to the baboons, we passed the main watering hole and 13 lions (adults and cubs) were gathered there. I was shaking with excitement that all of my photos of them are blurry, perhaps why I am not a professional photographer after all. No one on the team had ever seen so many lions together on site, truly amazing. I would never tire of seeing elephants, zebras, and giraffes though they were everywhere. It seemed like every direction you looked, if you let your eyes adjust for the distance, you could spot an elephant or giraffe. This trip inspired me to begin a tradition with my niece by sending her a stuffed animal of a species of wildlife I get excited over from each of my field trips. I sent her a little cheetah stuffed animal from this trip (she has a meerkat now too), and I can’t wait to teach her all about animals when I visit!

(Blurry lion photo is bottom right)

We would follow the baboons and collect samples until 11:30 AM, just as the temperatures were starting to get up there. At times we would have to cross into Tanzania to find a group, so the drive back to camp could be around 45 mins to an hour, with stops of course if we saw game. Lunch would be waiting from the amazing cook on site and was usually some form of leftovers from the tasty dinner the night before. We ate a lot of rice, beans, goat meat (had to get used to that one), and veg. They were impressed that I would eat anything that was made, including the goat, I guess since visitors tend to not try everything. The last time I had goat was a trip to Cyprus and I can’t say I love it, but don’t really mind it.

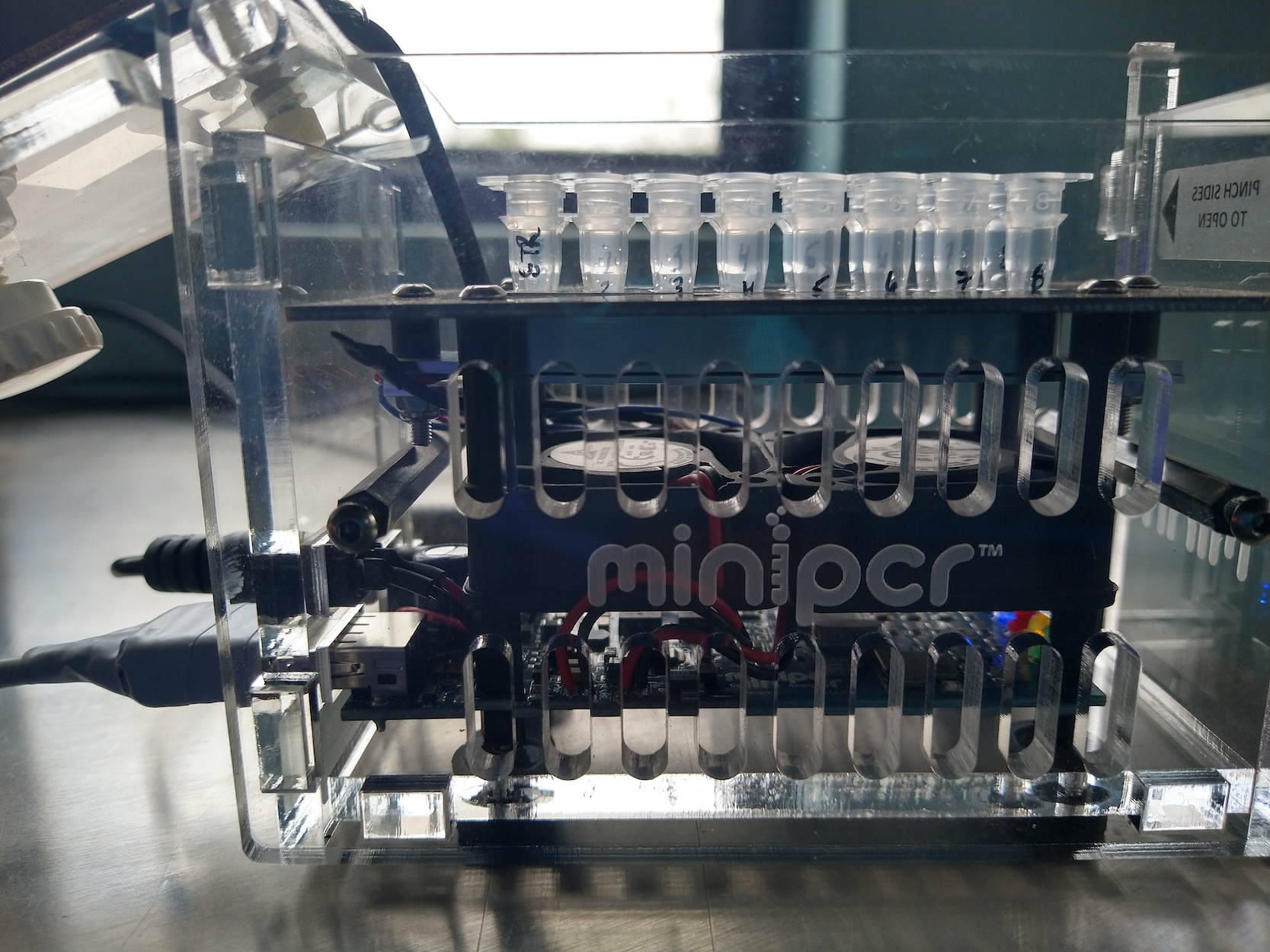

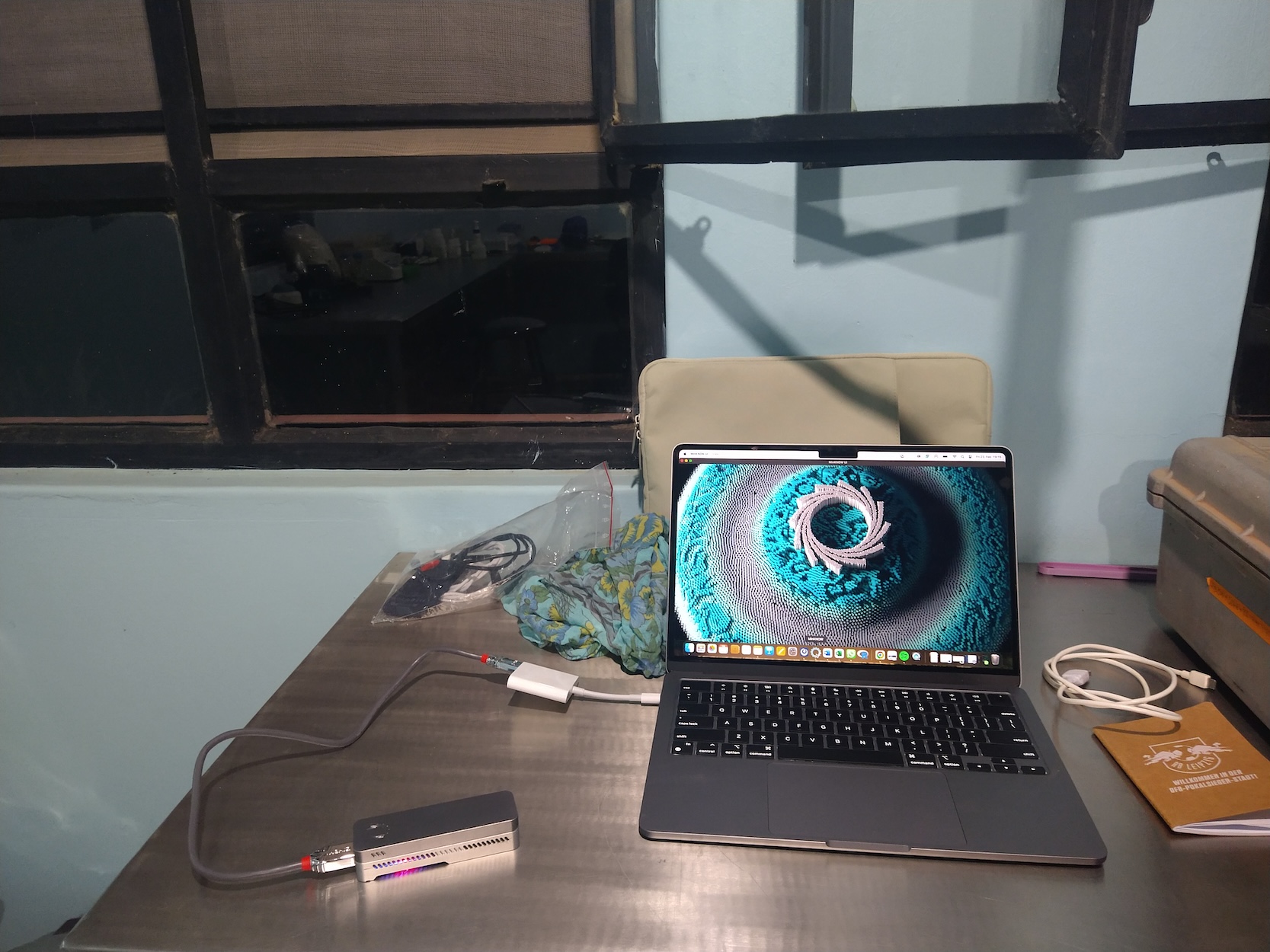

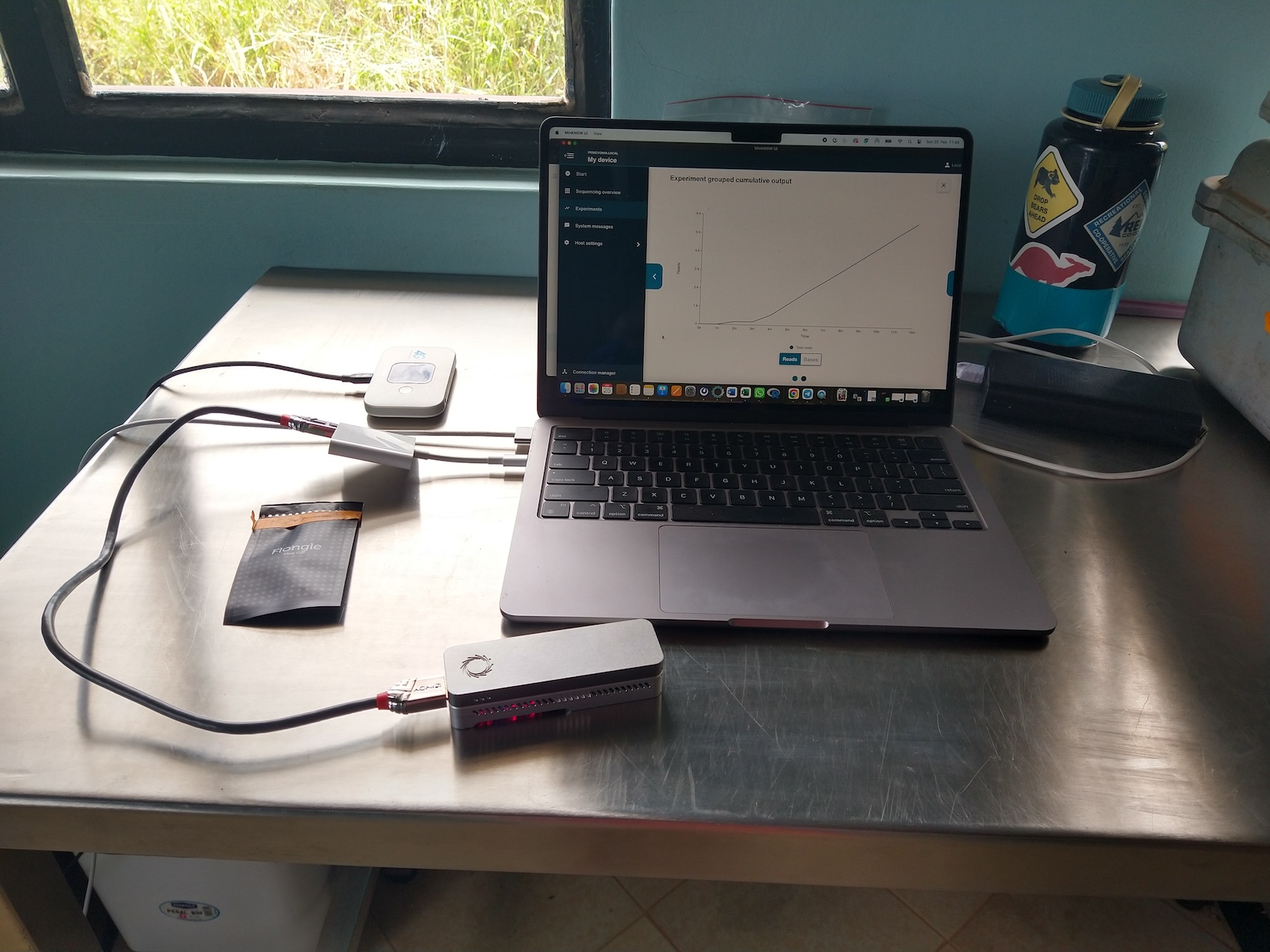

After lunch it was time for lab work and I would hide away from the strong sun in the little lab doing my experiments. It was still quite warm inside, I tried not to get any sweat into my reactions. Over those afternoons I extracted DNA from the fecal samples using a kit I brought down from Germany and some basic lab equipment like a mini centrifuge and heating block that were already there. Then, once I had the DNA, I would amplify it (make copies of regions I wanted) using a thermocycler in which the program ran off my phone, over Bluetooth! For the polymerase chain reaction to occur and for DNA to amplify this process needs to be repeated 1) the DNA needs to be heated up to 95C to denature it (separating the double strands) 2) cooled to a temperature ~55C where a primer (a short single stranded DNA fragment that is designed to bind to the start of your target DNA fragment) adheres to the DNA strand and 3) brought up to a temperature ~72C for an enzyme called taq polymerase to add bases on to the primer and complete the complementary strand of DNA. These cycles are repeated multiple times (~35 cycles) to generate many copies of DNA. The fact that there is a tiny machine that I could do this on, and run it off my phone, is amazing! Now that I had tons of copies of regions of the baboon DNA, I could sequence them and find the areas of mismatch to tell individuals apart as well as their relatedness. That’s where the little USB powered sequencer came in and, after a day of preparing the copies of DNA generated from 30 indivudal baboon samples, I was sequencing on my laptop, offline (not connected to internet) and generating gigabytes of sequencing data. The run was 24 hours long and with the wifi connection on site I could send the sequencing data to my colleague back in Germany to analyze. Wild! The analysis is still being developed, so it’s not quite complete yet. But my hope is that once the bioinformatic pipeline is established I can learn it and run it on my laptop on site… but I am not a bio-informaticist so it will have to really be fool proof before we can get to that point.

Some days the lab work would take in to the night. I would try to time my shower to not be in the direct heat of the day where I would just get sweaty again, but also not too late when it was cooling off and the water from the black tank wasn’t as heated up from the sun. The shower was an outdoor stall with a pully mechanism to pull up a bucket with a spout at the bottom. You fill this big bucket in a few trips with a smaller bucket from the tank. I love outdoor showers, if I ever have a house I will make one. We’d usually bring dinner back to our individual tents in tupper-wares to wind down from the day.

I was only on site for 10 days, but I had so many amazing experiences. My next trip to Amboseli is from mid July til the end of August, I’m really looking forward to spending a longer period there. I wasn’t really ready to leave! But, I returned to Nairobi and switched out the science bag for the mountain bag and headed North to Mount Kenya, more soon 🙂

I am truly at a loss for words, Kelly. Your experiences and especially your intelligence blow me away! I don’t pretend to know most of what you are actually doing, but it fascinates me to hell! A young girl from Grand Island NY knowing and doing what you do is super impressive. And I LOVE your idea of sending Sydney reminders of her Aunt Kel Kel. Venture on, my beautiful niece and as always, be safe!

(I can only dream of seeing all the animals you have had close contact with!)

Aunt Pap

LikeLiked by 1 person

LikeLiked by 1 person